Design Decisions & Tradeoffs

Having explored Frame’s architecture, let’s examine the key design decisions that shaped its implementation.

Embracing Serverless

A significant design decision was adopting the serverless computing model as the primary method for executing Frame’s application code. In serverless architecture, the cloud provider handles server provisioning, scaling, and maintenance.

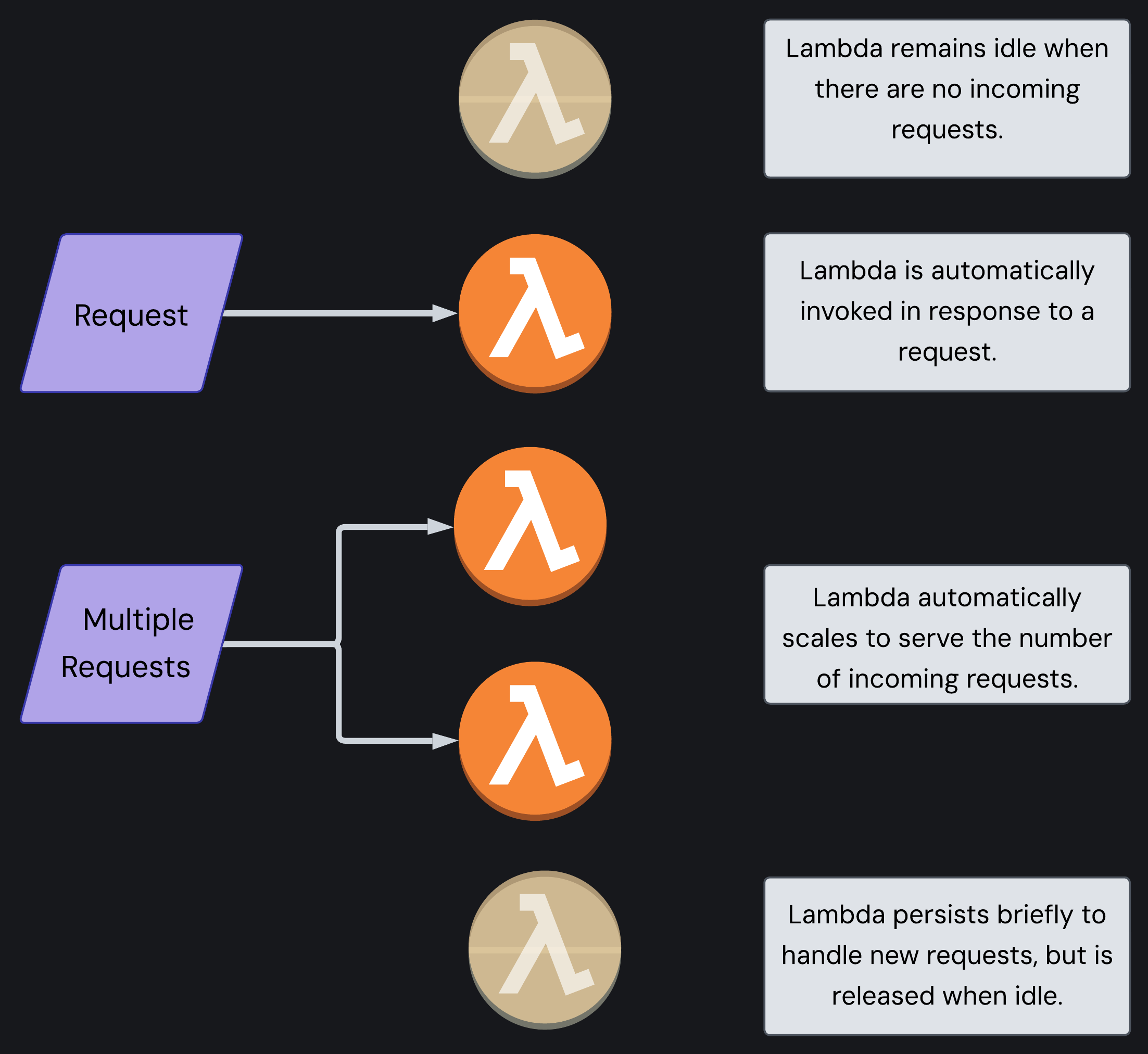

Serverless computing centers on Function-as-a-Service (FaaS), such as AWS Lambda. Lambda functions are triggered by specific events like HTTP requests. When a request occurs, AWS allocates the necessary resources (physical server(s)) to process the event and execute the function. If there are no incoming events, no servers are allocated, and when processing completes, any resources are released.

Serverless request handling patterns: idle state, automatic invocation for single requests, automatic scaling for multiple requests, and release when processing completes

Why Serverless?

This model offered several compelling benefits for Frame:

- Developers are freed from server management responsibilities. The cloud provider handles all provisioning, scaling, updating, and maintenance tasks.

- Automatic scaling to match demand, with no costs incurred during periods of inactivity. This differs from a server-centric approach, where an organization may pay for an allocated server even if it is idle.

- Built-in redundancy and fault tolerance are provided by the cloud provider.

These benefits aligned with Frame’s goal of providing a simple, easily deployed, easily managed solution with a low barrier to entry.

The Tradeoffs

No architectural decision comes without tradeoffs, and serverless is no exception:

- Cold Start Latency: After periods of inactivity, AWS needs to provision hardware when a new request arrives, creating a brief delay known as a “cold start”. While this delay is usually negligible for most applications, it can affect latency-sensitive use cases. It is important to note that this Lambda cold start problem is separate from the recommender system cold start problem referred to earlier in this case study.

- Technical Resource Limitations: Memory and performance constraints of serverless functions impose strict limits on available memory, execution time, and CPU power. For Frame’s image processing needs, these limits are more than sufficient, but they might be restrictive for other specialized workloads.

- Limited Customization: Serverless environments provide fewer configuration options than traditional server deployments. While customizing runtime environments or implementing specialized libraries is more restricted, this simplicity has reduced operational complexity.

Alternatives Considered

Before committing to a serverless architecture, we evaluated:

- Container-Based Platforms (such as AWS Fargate): Enable deployment of containerized applications without directly managing the underlying server infrastructure. This provides more control over the environment than serverless functions and offers flexibility and support for long-running processes. However, it introduces more configuration overhead, requiring management of container builds and deployments. For Frame’s event-driven workloads, this felt like unnecessary complexity.

- Virtual Machines (such as AWS EC2 instances): Provide maximum control over the environment and runtime but require significant operational effort, including provisioning, scaling, and patching servers. These downsides run contrary to Frame’s goal of creating a low-maintenance solution.

Ultimately, serverless struck the right balance: minimal operational overhead, cost-effective scalability, and seamless deployment.

Using SQS for Reliable Image Processing

Another key decision was implementing asynchronous processing for image ingestion. Since image processing is both compute-intensive and potentially error-prone, a reliable solution that could handle traffic spikes, provide fault tolerance, and maintain responsiveness even under load was needed.

An SQS queue was placed between the API Lambda and Image Ingestion Lambda to serve as a buffer. This architectural decision significantly enhanced both system stability and user experience.

Why SQS?

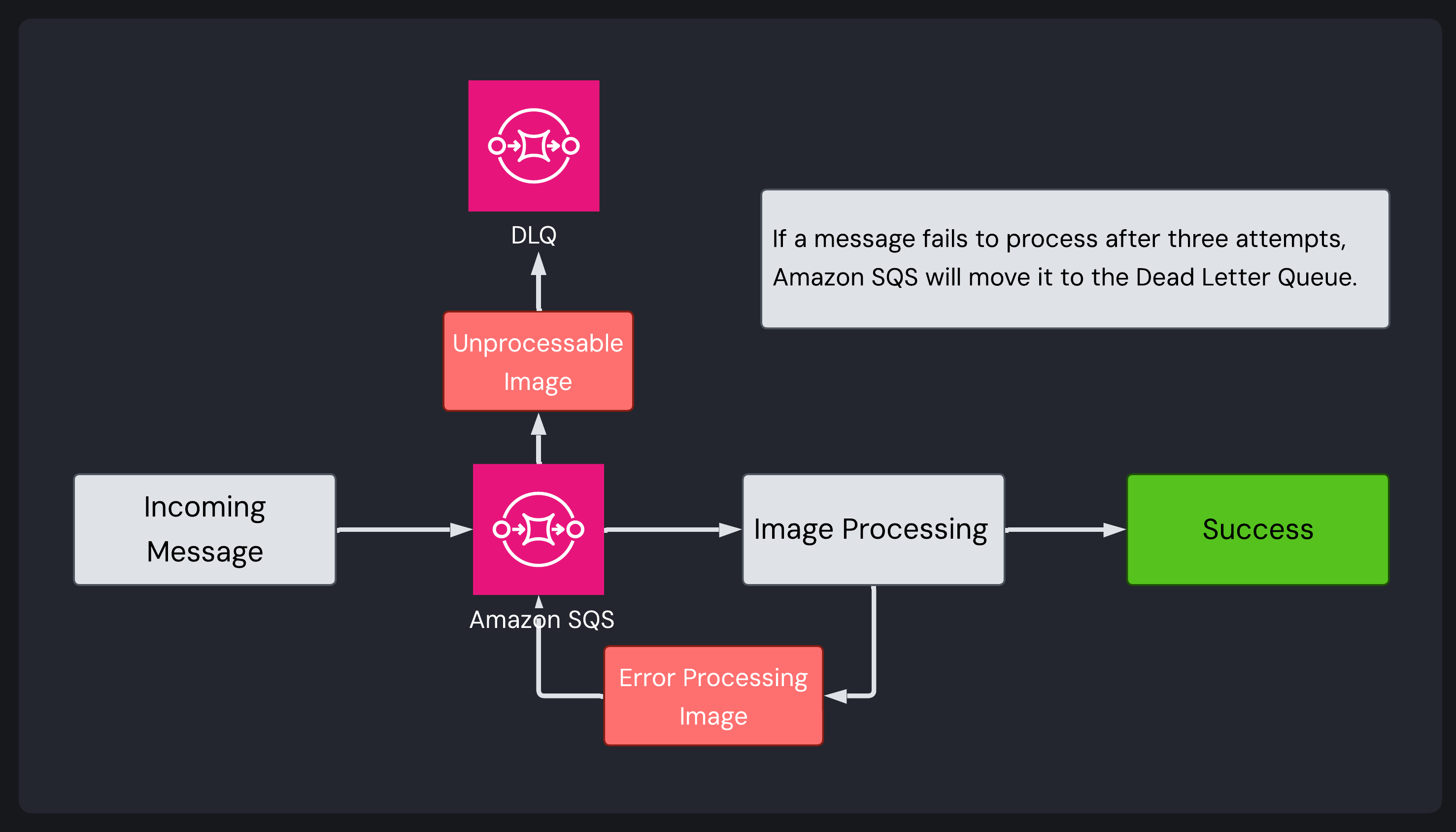

SQS automatic retries and error handling: If image processing fails, it is automatically retried. If it fails three times, it is redirected to a Dead Letter Queue for troubleshooting.

SQS offered several benefits that aligned perfectly with the image processing needs of Frame’s target users:

- Fault Tolerance & Retry Capability / Robust Error Handling: SQS provides automatic retry capabilities that are invaluable for handling transient failures. If the Image Ingestion Lambda fails to process a message, the message returns to the queue after a configurable visibility timeout and can be retried automatically. After three failed processing attempts, messages are automatically moved to a Dead Letter Queue (DLQ), creating a persistent record of problematic images for troubleshooting.

- Independent Scaling of Components: By decoupling the API from the image processing logic, each component could scale independently based on its specific workload. The API Lambda can handle high volumes of incoming requests without being bottlenecked by the more resource-intensive image processing operations.

- Decoupled Processing: The queue acts as a buffer between receiving requests and processing them, allowing the API Lambda to validate incoming images and immediately return a response to the user, while the actual processing happens asynchronously.

- AWS-Native Integration: As an AWS-native service, SQS integrates seamlessly with Frame’s architecture, meaning less configuration, less maintenance, easier deployment, and better observability.

The Tradeoffs

The decision to use SQS did come with some tradeoffs:

- Eventual Consistency: Images will be processed, but the system cannot guarantee exactly when. This means that, immediately after uploading, a search might not include the newly uploaded image.

- Message Size Limitations: SQS has a 256KB message size limit, requiring the use of image URLs rather than raw image data.

- At-Least-Once Delivery: Standard SQS queues provide an “at-least-once” delivery guarantee, not “exactly-once” delivery. This means that, in rare circumstances, the same image could be processed multiple times. To mitigate this, Frame includes idempotency checks when storing embeddings. If an image and description combination already exists in the database, a duplicate entry is not created. Instead, the existing entry is updated or the insertion is skipped completely, ensuring data consistency despite SQS’ delivery semantics.

Alternative: Step Functions

AWS Step Functions were considered as an alternative for orchestrating the image processing workflow. Step Functions excel at complex workflows with multiple stages and conditional logic.

However, for Frame’s process, Step Functions introduced unnecessary complexity as the workflow is linear and doesn’t require complex branching or conditional logic.

Frame needed a buffer with retry capabilities rather than a complex multi-step orchestration tool, which SQS provided with minimal configuration.

Supporting Local File Uploads for Image-Based Search

Frame’s third key design decision addressed how users could search with local image files. While URL-based image search is powerful, many users want to search using images stored directly on their devices. The solution needed to allow file uploads without compromising the API’s simplicity, reliability, or performance.

The Solution: Temporary S3 Storage

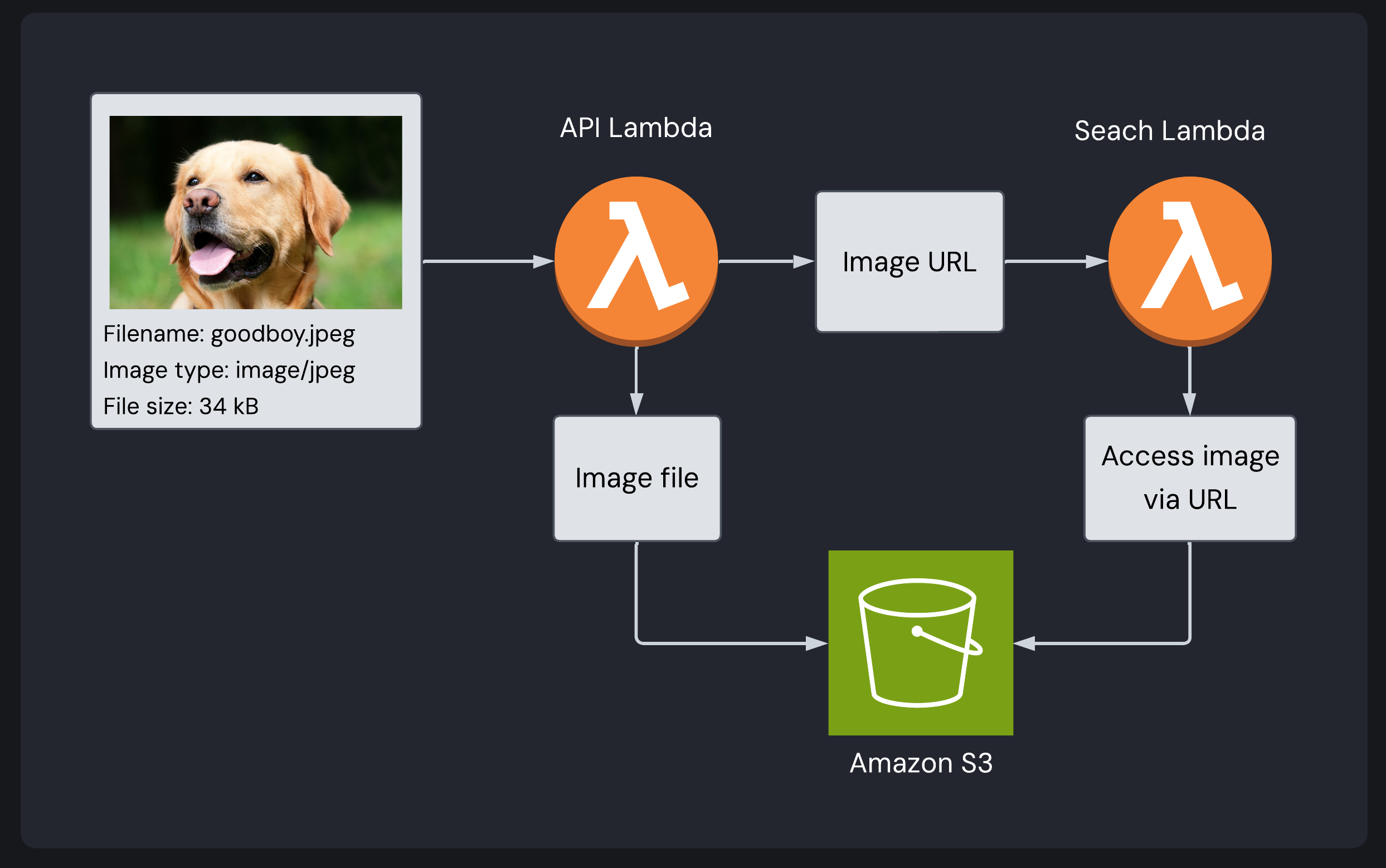

After evaluating several approaches, a solution was developed using Amazon S3 (AWS’s native object storage service).

- When a user uploads an image file for search, the API Lambda stores it temporarily in S3.

- S3 makes the image available via URL.

- This URL is passed to the Search Lambda, which processes it like any other URL.

- The temporary image is deleted from S3 after search completion.

Frame’s temporary S3 storage solution for search image file uploads: image stored in S3 (so the associated URL can be obtained) and deleted following search completion

Alternative: base64

One alternative was to encode the image file as a base64 string and include it directly in the search request payload. However, base64 increases the payload size by 33%, limiting acceptable images to 4.5MB due to Lambda’s 6MB payload limit. Additionally, decoding large base64 strings within the Search Lambda could hurt performance, consuming valuable processing time and memory.

Why S3?

The S3 approach creates a unified image processing and search path for both file and URL-based search, maintaining architectural simplicity and consistency while addressing the unique challenges of file uploads. Deleting images after search completion also prevents unnecessary storage costs or orphaned files.