From Theory to Practice - Building an Image Search System

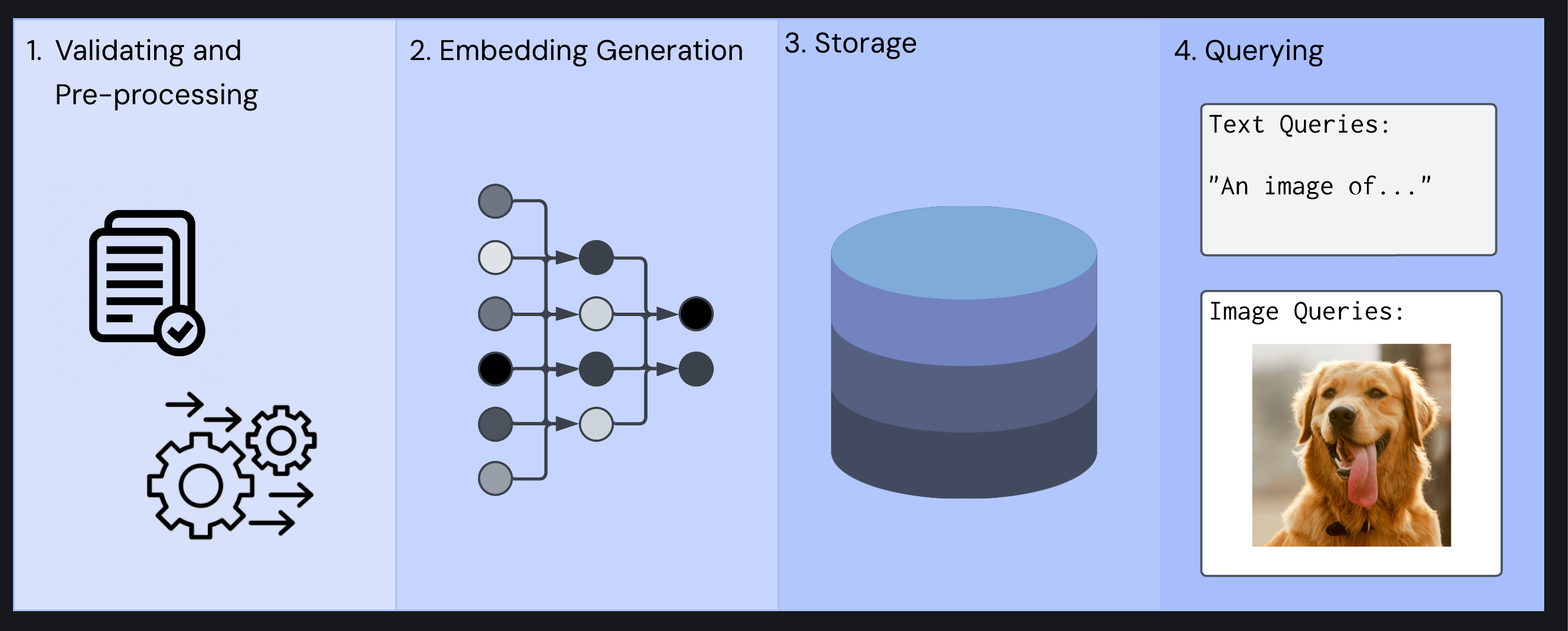

Modern businesses often accumulate vast image collections. Existing search functionality typically relies on associated text data like titles and descriptions. However, users now expect more intuitive search capabilities - searching by uploading similar images, using nuanced text descriptions, or combining both. With computational costs steadily declining, implementing multimodal embeddings has become increasingly viable from a business perspective and would dramatically improve search capabilities. However, it requires addressing several interconnected technical challenges: validating and pre-processing input data, generating embeddings, storing embeddings, and querying stored embeddings. The following sections will break down each of these challenges in more detail.

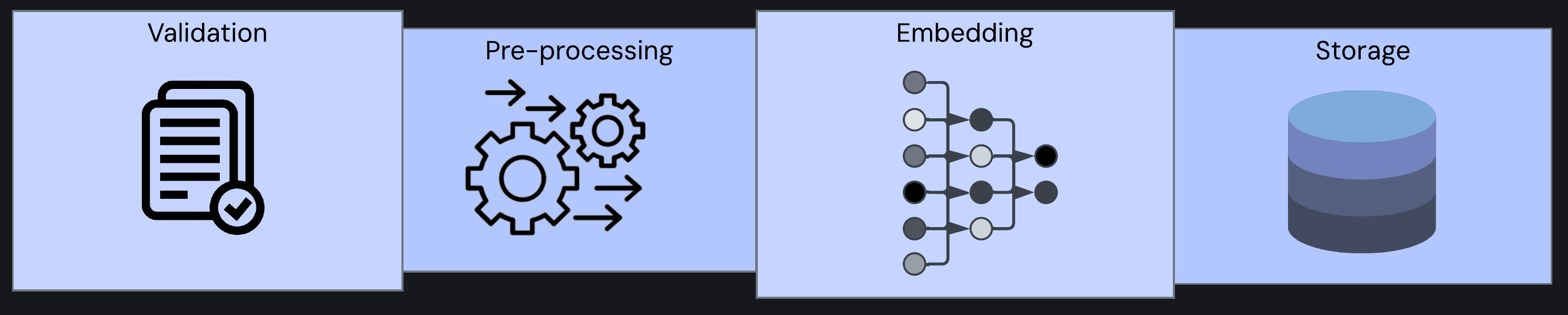

Four-step image search system workflow: 1. validating and pre-processing, 2. embedding generation, 3. database storage, 4. querying with text and image

1. Validating and Pre-processing

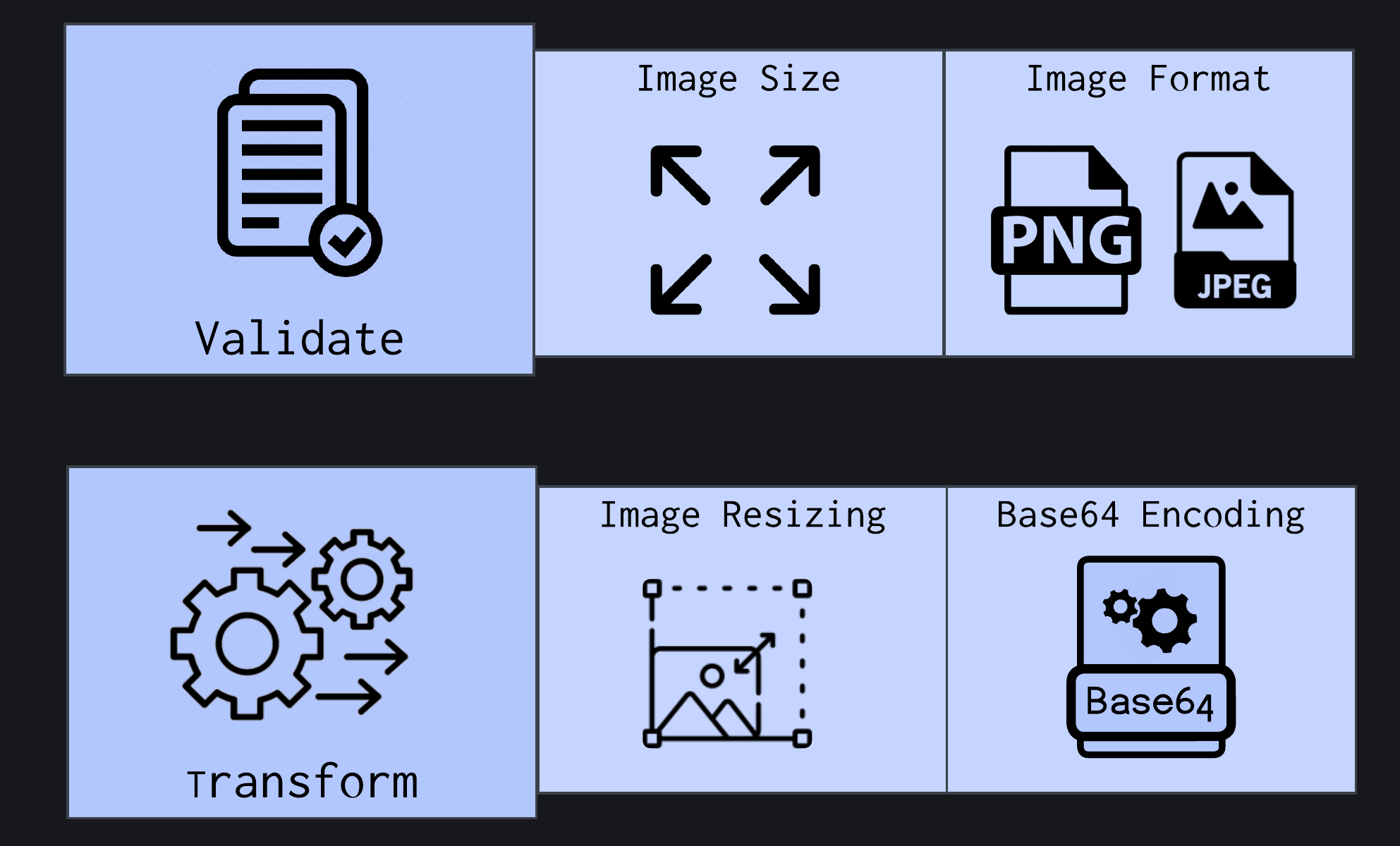

The first challenge is handling input data. Users send images in varying formats (JPEG, PNG, WebP), sizes, and resolutions. The system must validate the input data and then prepare images for the embedding model through specific transformations:

- Images often need to be converted to buffers (a low-level binary representation of image data), as many image processing libraries require this binary format for pre-processing.

- Images must be pre-processed, including resizing images to the dimensions expected by the model. This is a critical step to ensuring consistent and high-quality embedding outputs. Embedding models are sensitive to input shape and quality. Inconsistent image inputs, such as varying aspect ratios or non-standard file types, can degrade the performance and semantic accuracy of the resulting embeddings.

- Images must be serialized for transmission over the network to an embedding model API. This serialization is typically accomplished through base64 encoding, which converts the binary image data into ASCII text characters that can be safely included as a string inside a JSON payload that the embedding model can process.

Two-stage image validation and pre-processing workflow: 1. Validation (checking size and format), 2. Transformation (resizing and base64 encoding)

2. Embedding

Beyond pre-processing, the next critical decision lies in selecting the appropriate embedding model.

Fewer options exist for multimodal capabilities than for text-only use cases. Models like OpenAI’s CLIP or Amazon’s Titan Multimodal G1 offer multimodal capabilities with different tradeoffs in speed, accuracy, hardware requirements, and licensing terms.

Developers must consider various deployment approaches for these models, from cloud-based hosted services to self-managed infrastructure. Each approach offers different trade-offs between convenience, control, cost, and performance. Ultimately, the right choice depends on the specific project requirements related to latency, scale, budget, and operational resources.

3. Storage

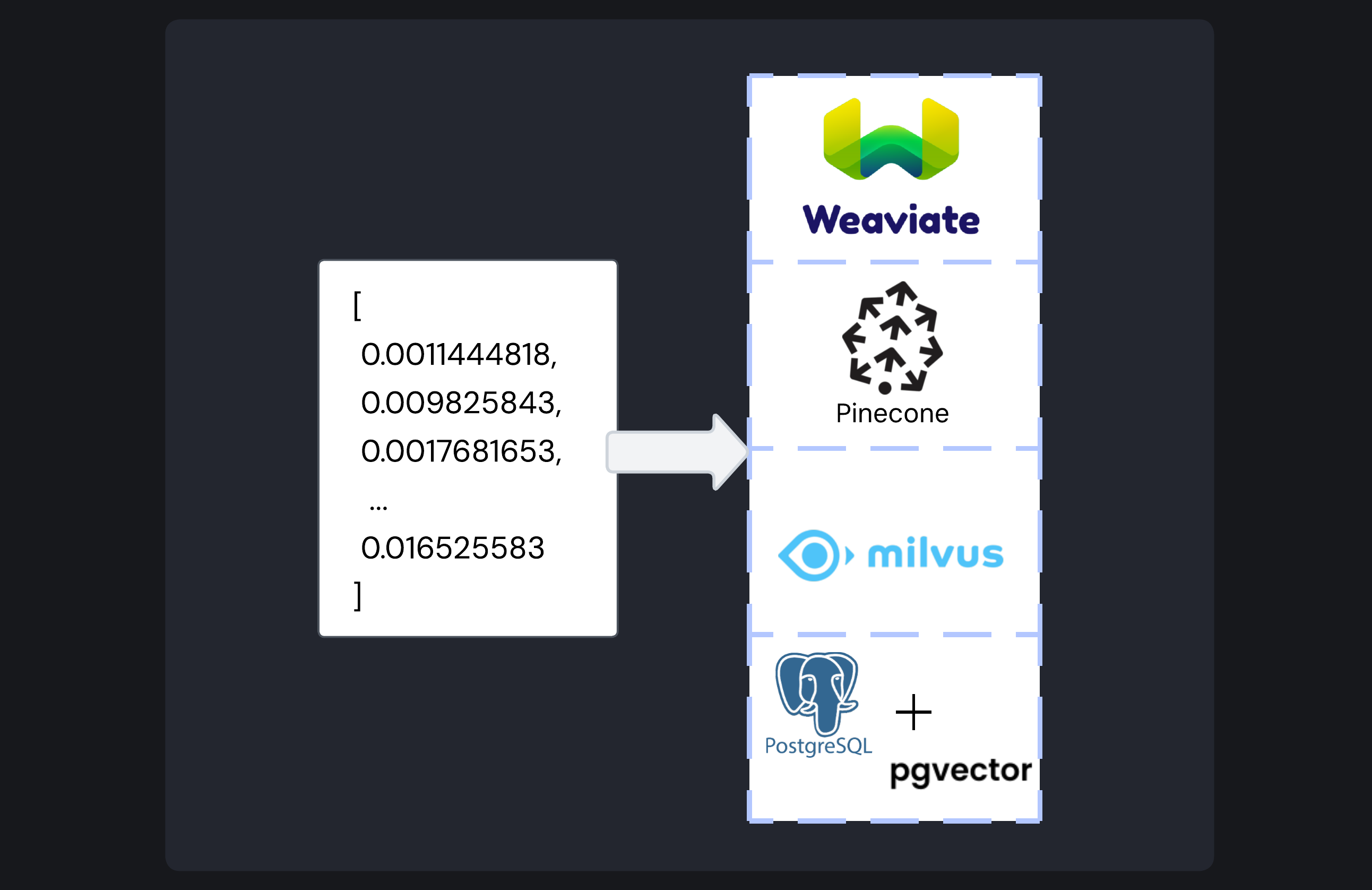

Once embeddings are generated, they must be stored in a way that enables efficient similarity search.

Vector embeddings can be stored in purpose-built vector databases (Pinecone, Weavite, Milvus) or traditional databases extended for vector functionality (PostgreSQL + pgvector)

Vector databases are a special class of database engineered specifically for the efficient storage and retrieval of embedding vectors.1 Developers typically choose between two primary approaches: purpose-built vector databases and traditional databases with vector extensions.

-

Purpose-Built Vector Databases: Platforms like Weaviate, Milvus, and Pinecone are designed from the ground up specifically for vector operations. These specialized databases offer several advantages:

1.1. Optimized specifically for high-dimensional vector similarity search.

1.2. Support for multiple advanced indexing algorithms (HNSW, IVF, DiskANN, CAGRA).

1.3. Excel with massive vector collections requiring sub-millisecond query times.2 -

Extended Traditional Databases: Established database systems have evolved to incorporate vector capabilities. For example, PostgreSQL provides a pgvector extension3 that allows organizations to integrate vector operations within a mature, battle-tested database engine. This traditional approach offers several advantages:

2.1. Maintains compatibility with existing ecosystems and tooling.

2.2. Preserves ACID compliance, transactions, and familiar SQL query patterns.4

2.3. Enables storing vector data alongside conventional relational data.

2.4. Supports common indexing methods like HNSW and IVF (discussed in greater depth below).

2.5. Sufficient performance for most real-world applications.

Most vector databases offer K Nearest Neighbor (KNN) and Approximate Nearest Neighbor (ANN) search approaches. KNN compares the search vector against every vector stored in the database,5 guaranteeing perfect accuracy but at a high computational cost. ANN, by contrast, employs intelligent indexing algorithms like Hierarchical Navigable Small World (HNSW) and Inverted File Index (IVF) to dramatically reduce the search space, sacrificing some accuracy for response speed.

Generally, KNN should be used in scenarios where precise (100% accurate) nearest neighbor identification is crucial. However, since KNN becomes extremely slow and computationally expensive when datasets expand beyond a certain size, ANN algorithms are essential for most production-grade semantic search applications.6

The vector database space offers numerous options, each with distinct advantages and limitations that should be carefully evaluated based on the context of the specific use case.

4. Querying

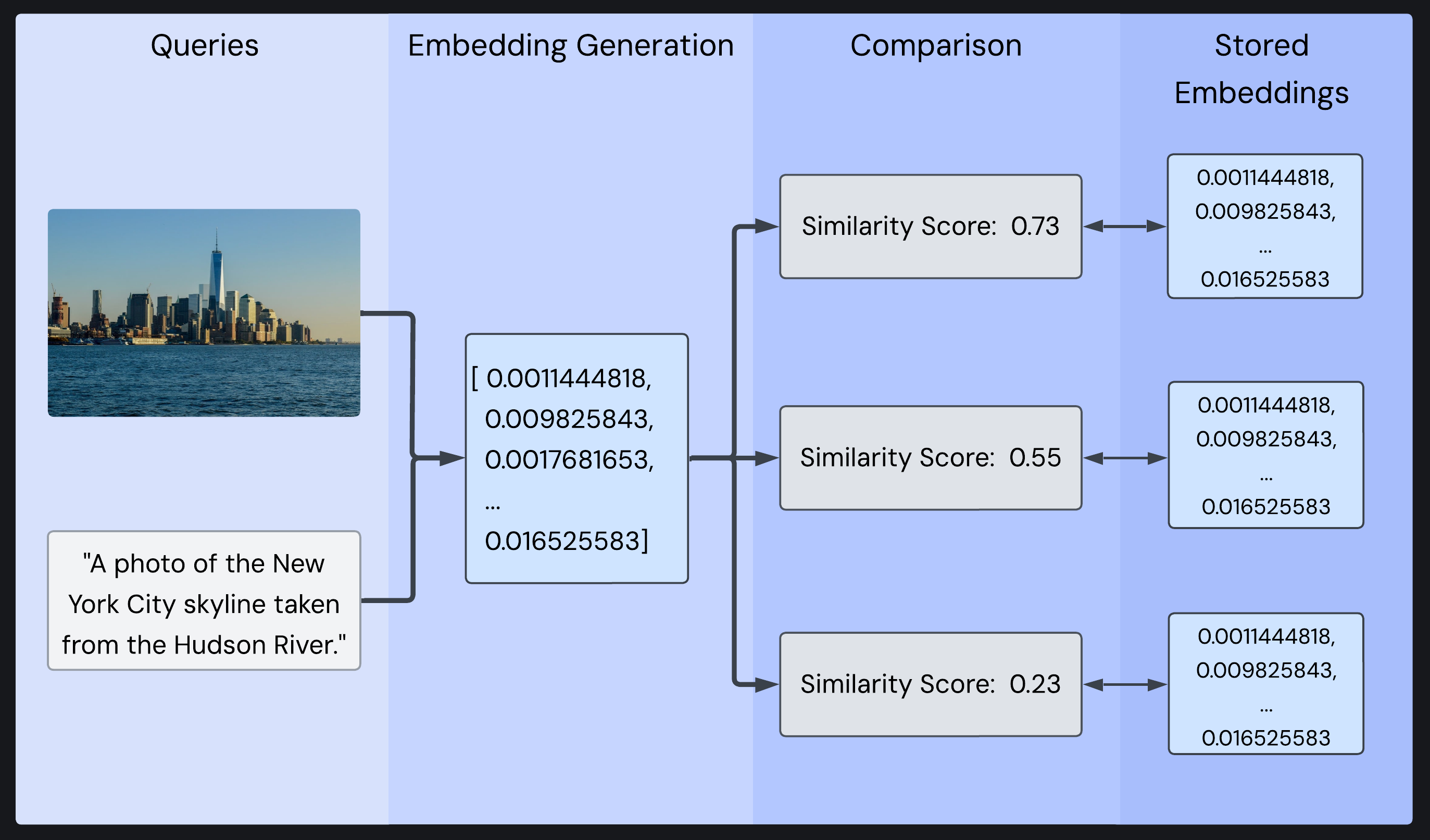

When a user submits a search, their input (which may be text, image URL, locally stored image, or a combination) must go through the same embedding process as the stored images before any comparison can happen. For text queries, this is straightforward. However, for image queries, users may provide images in different ways. While some users might have image URLs, a user searching for similar images is much more likely to have the query image stored locally on their device. This creates the additional challenge of handling image file uploads, which is discussed in greater depth below.

Query inputs (image and optional text description) are converted to an embedding, then compared against database embeddings to generate similarity scores

Once embedded, the query embedding is compared against the database using a similarity metric. Most vector databases and libraries support common similarity metrics, including dot product, cosine similarity, and Euclidean distance. As mentioned, cosine similarity is particularly valuable for semantic search as it measures directional similarity regardless of vector magnitude.

Additionally, a production-grade system should ideally support the configuration of minimum similarity thresholds to filter out low-confidence matches. If precision is a critical concern, implementing reranking techniques can enhance result quality.

The Complete Picture: Connecting the Components

This examination of a complete multimodal embedding system reveals that building one from scratch is a significant undertaking. While each function - validation, processing, embedding, storage - presents its technical challenges, additional complexity lies in connecting these components into a cohesive whole.

Complete multimodal embedding system: validation, pre-processing, embedding, and storage

An “embedding pipeline” must feature error handling, retry mechanisms, and scalability to function reliably in production. While stitching together these components manually offers maximum flexibility, it quickly becomes time-consuming, error-prone, and difficult to scale and maintain.

Navigating the Landscape: Existing Solutions

Given the challenges of building from scratch, several solutions have emerged:

1. Managed Cloud Solutions

Services like Marqo provide a managed cloud solution that abstracts away the infrastructure complexity, allowing developers to access vector generation, storage, and retrieval through a single API.

While Marqo boasts many additional features, such as different embedding models, custom fine-tuning for those models, and low search latency, this can be redundant for many use cases. The rich feature set comes with corresponding configuration complexity and cost, with solutions starting at a minimum of $500 per month (before considering the cost of provisioning the infrastructure). This is unlikely to align with the needs of cost-minded small businesses.

2. Open-Source Solutions

Marqo also offers an open-source, self-hosted solution, providing potentially lower long-term costs. This solution involves deploying Marqo’s infrastructure onto an organization’s preferred cloud provider (Azure, Google Cloud, or AWS) via Kubernetes clusters. While a great solution, three requirements made deployment significantly more complex:

- Expertise in deployment with Kubernetes and Helm (including experience with the managed Kubernetes service on the cloud provider of choice - AKS, GKE, or EKS).

- Multiple interconnected components, each with a steep learning curve (Kafka, Vespa.ai, Maven, PyTorch).

- Since Marqo loads embedding models into memory, its design requires memory-optimized instances for production workloads. These additional RAM requirements can lead to substantial infrastructure costs even when idle.

This approach is well-suited and optimized for high scalability and accommodating extensive data and traffic loads. While this approach suits mature companies with dedicated resources and expertise, it creates a high barrier to entry for smaller teams. These smaller teams, working with modest data volumes, typically don’t need extensive configuration or advanced scalability and performance features.