The Challenge of Organizing Images

When working with text, organizations benefit from language’s natural structure and searchability via keywords, tags, headings, and full-text search. In contrast, image organization systems must first analyze inherently unstructured visual data that lacks text’s built-in cues.

The Traditional Approaches

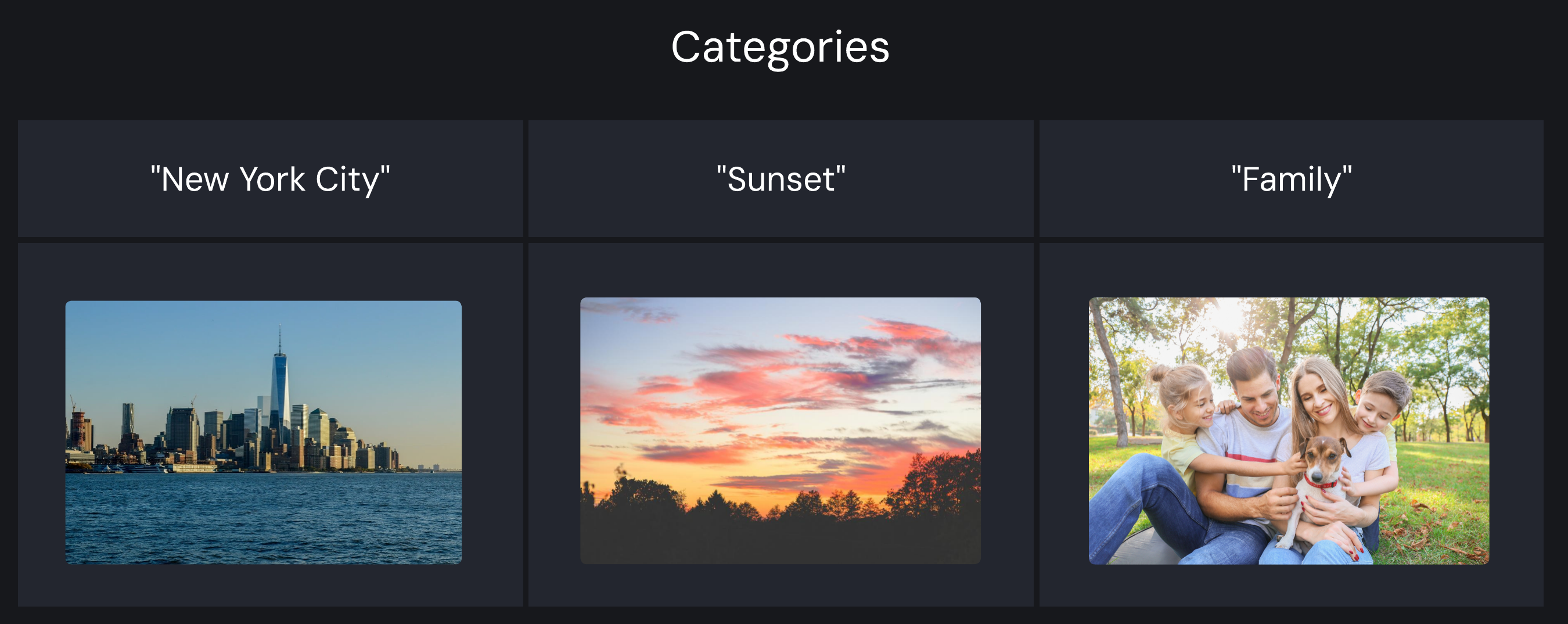

1. Manual Labeling / Categorization

The simplest way to address the problem of organizing images is to have human curators or users assign keywords, tags, titles, categories, and captions to images, labeling them with terms like “sunset,” “portrait,” or “New York City” to enhance searchability. Unfortunately, this process is time-consuming, subjective, and inconsistent, as different people may describe the same image differently. This inconsistency, combined with the reliance on humans to manually provide these labels for every image, creates significant challenges for search systems attempting to deliver reliable, consistent, high-quality results.

Further, as the number of images within a category grows, it can become difficult for a user to find the most relevant results, as labeling does not provide a way to rank the image’s relevance within the label/category. How does a user find the most relevant sunset image when hundreds share the same tag?1

While image labeling has limitations, it remains prevalent in advanced image search systems today, particularly when combined with other methods.

2. User Behavior

To address the issue of unranked results, some companies implement systems that incorporate user behavior to rank search results. Shutterstock, for example, uses behavioral data like downloads as implicit feedback to assess and rank image quality. This approach helps the system identify which images a user finds valuable for specific searches, refining future recommendations.

Ranking based on download counts: popular content appears while new content is buried

One downside to this approach is known within recommendation systems as the “cold start” problem - when new images are added, they lack significant user data. Without this data, these images are unlikely to appear near the top of search results, creating a chicken-or-the-egg situation where users can’t discover new content because it hasn’t been previously discovered. This can significantly limit the visibility of newly added images, regardless of their potential relevance or quality.2

Both manual labeling and incorporating user behavior have fundamental limitations in how they represent images for search. Manual labeling captures only the explicitly tagged aspects, creating a sparse representation limited by vocabulary and time constraints. User behavior data, while valuable, only reflects how users have interacted with images they have already discovered, often leaving new content at a disadvantage regardless of relevance.

Understanding Embeddings

Instead of relying on manual labels or user behavior, what if software could actually “understand” the visual content of images? Neural networks and image embeddings now make this possible.

A neural network is a machine learning program or model that makes decisions that resemble how the human brain functions, using processes that imitate how biological neurons collaborate to identify patterns, evaluate options, and draw conclusions. In particular, neural networks can identify patterns in data (like objects in images or the semantic meaning of sentences) and recognize abstract qualities (like mood or style). This is possible because the network discovers patterns by analyzing millions of images during training. For example, a well-trained neural network can learn that certain combinations of color, lighting, and compositional elements evoke certain moods, identifying a vibrant Tokyo city scene as “energetic”.

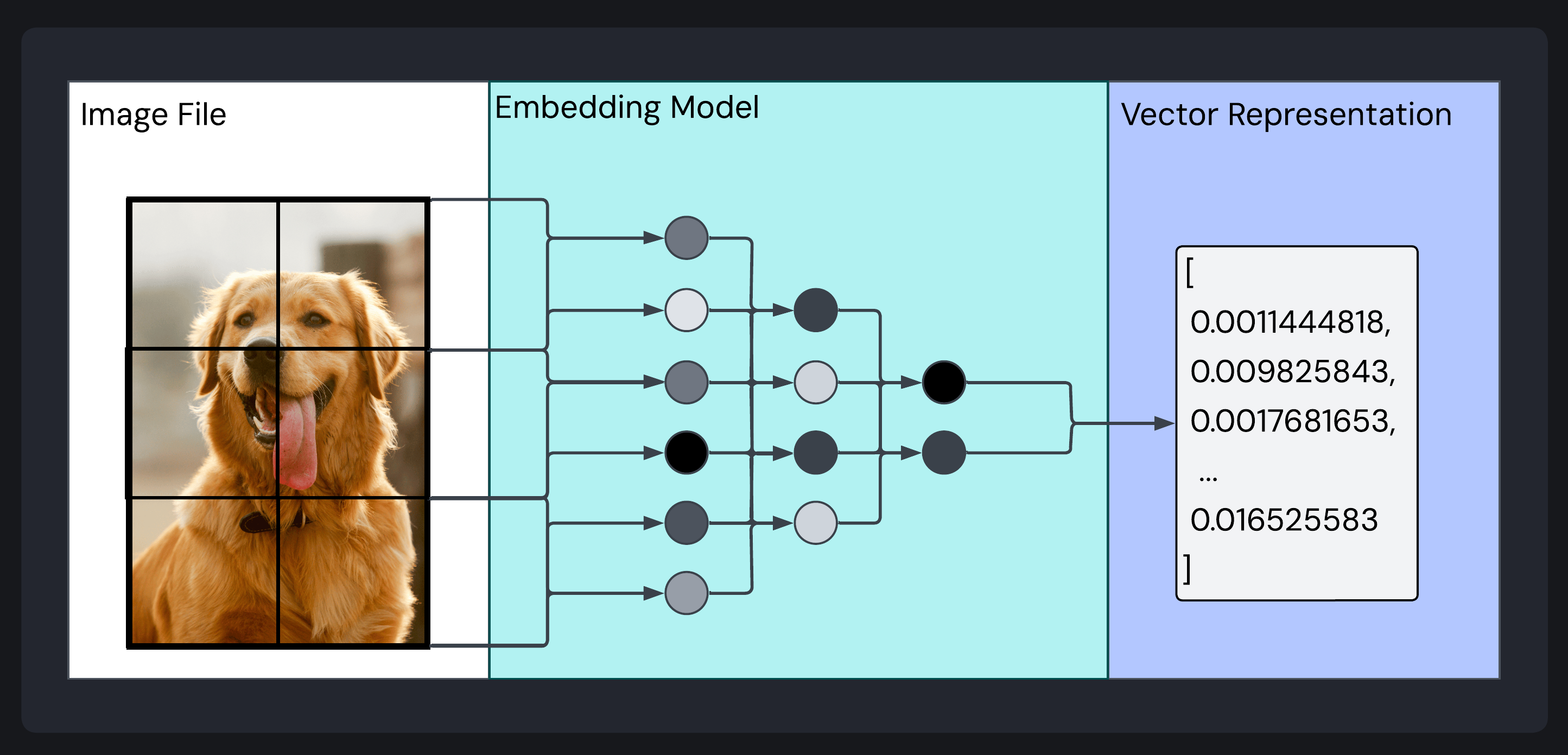

An image of a dog transformed through an embedding model into its lower-dimensional vector representation

Within this broader family of neural networks, specialized architectures called embedding models serve to convert large, detailed pieces of unstructured data (like an image) into a structured list of numbers. This list is referred to as an embedding.

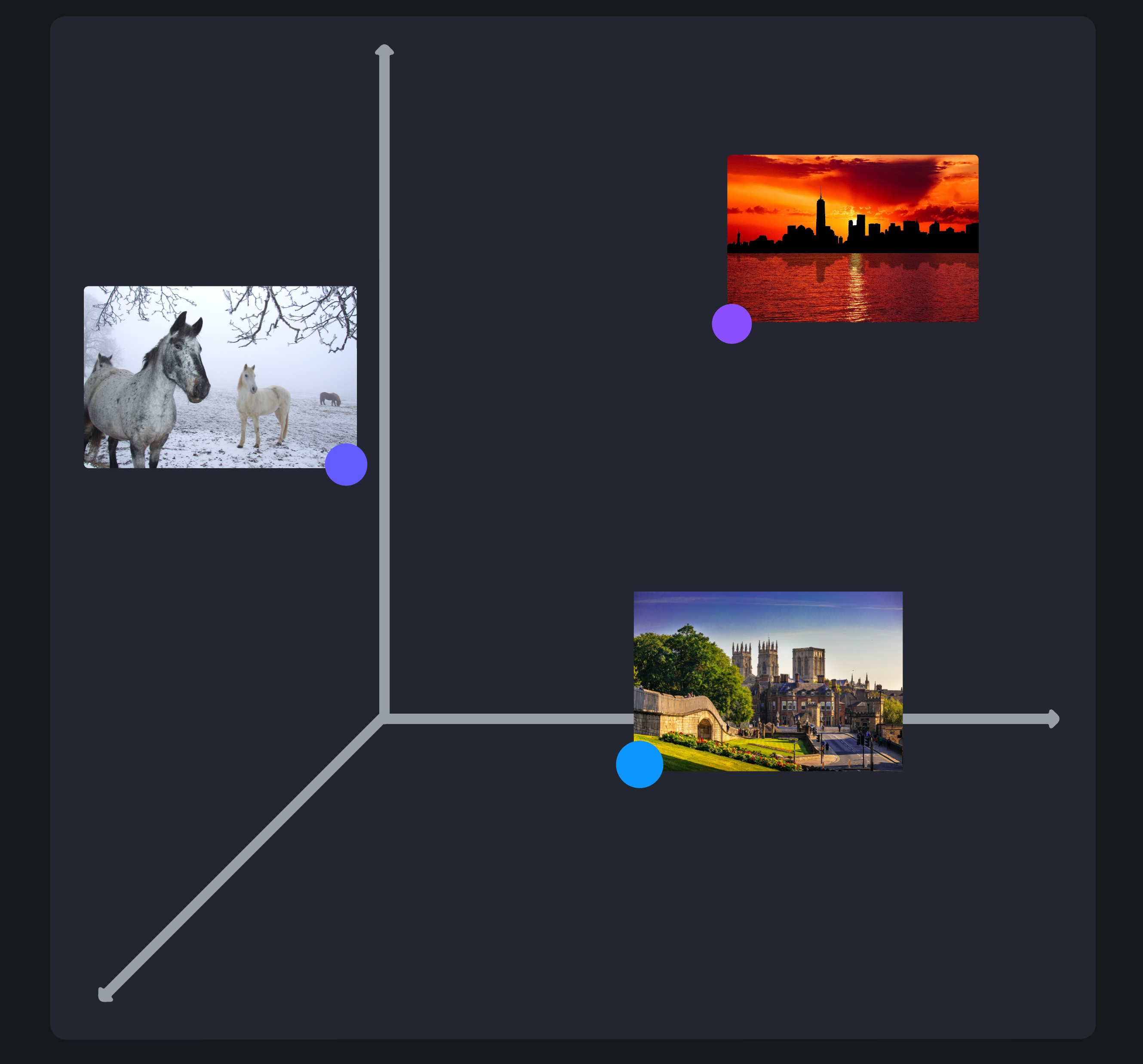

An embedding is a mathematical vector. For example, a 2D vector (like [3, 4]) represents a position in two-dimensional space, identified by two numbers: an x-coordinate (3) and a y-coordinate (4). This can be easily visualized on a flat surface.

If a third number is added, a 3D vector (say, [3, 4, 2]) is created with an additional z-coordinate (2). This can still be visualized as a point floating in a room.

Each number represents a specific feature or aspect of the original data, capturing tangible features (objects, colors) and intangible qualities (mood, style). An embedding fundamentally acts as a digital fingerprint or blueprint that captures the key identifying elements of some unstructured data, including what it contains, how its compositional elements relate to each other, and the feeling it evokes.

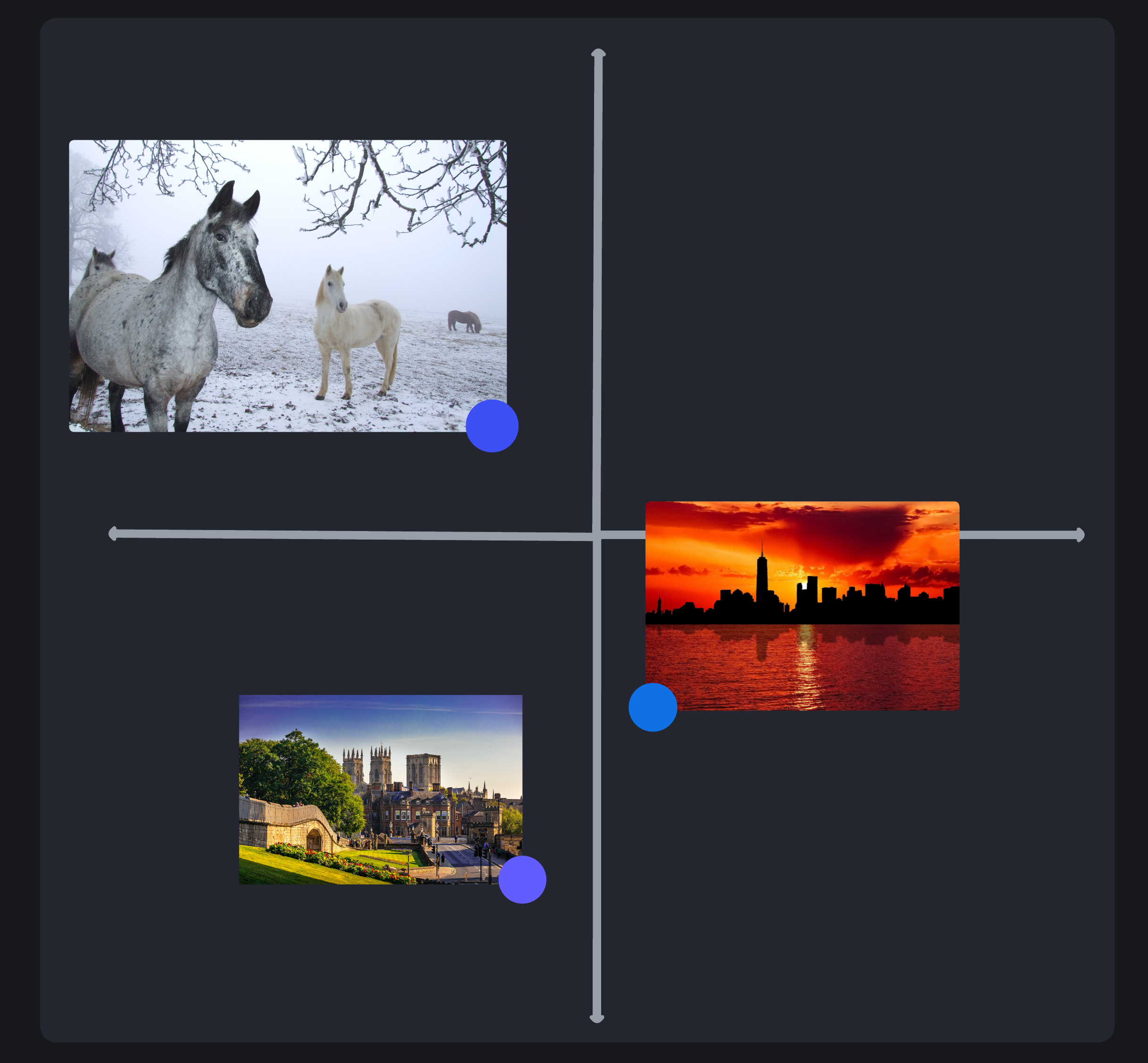

However, vector embeddings often exist in multiple dimensions (sometimes containing over 1,000 numbers), allowing them to be positioned in a “high-dimensional” space. The numbers that make up the embedding are interpreted as coordinates within this high-dimensional space. While it’s impossible to visualize a 1,024-dimensional space, the principle remains the same. Each embedding sits at a single point in this abstract high-dimensional space. That point is determined by the numbers that make up the embedding.

This is important because images with similar visual characteristics (colors, shapes, objects, composition, etc.) end up positioned close to each other in this abstract, high-dimensional space. Mathematical techniques, like cosine similarity, can then be used to find images most similar to a reference image.

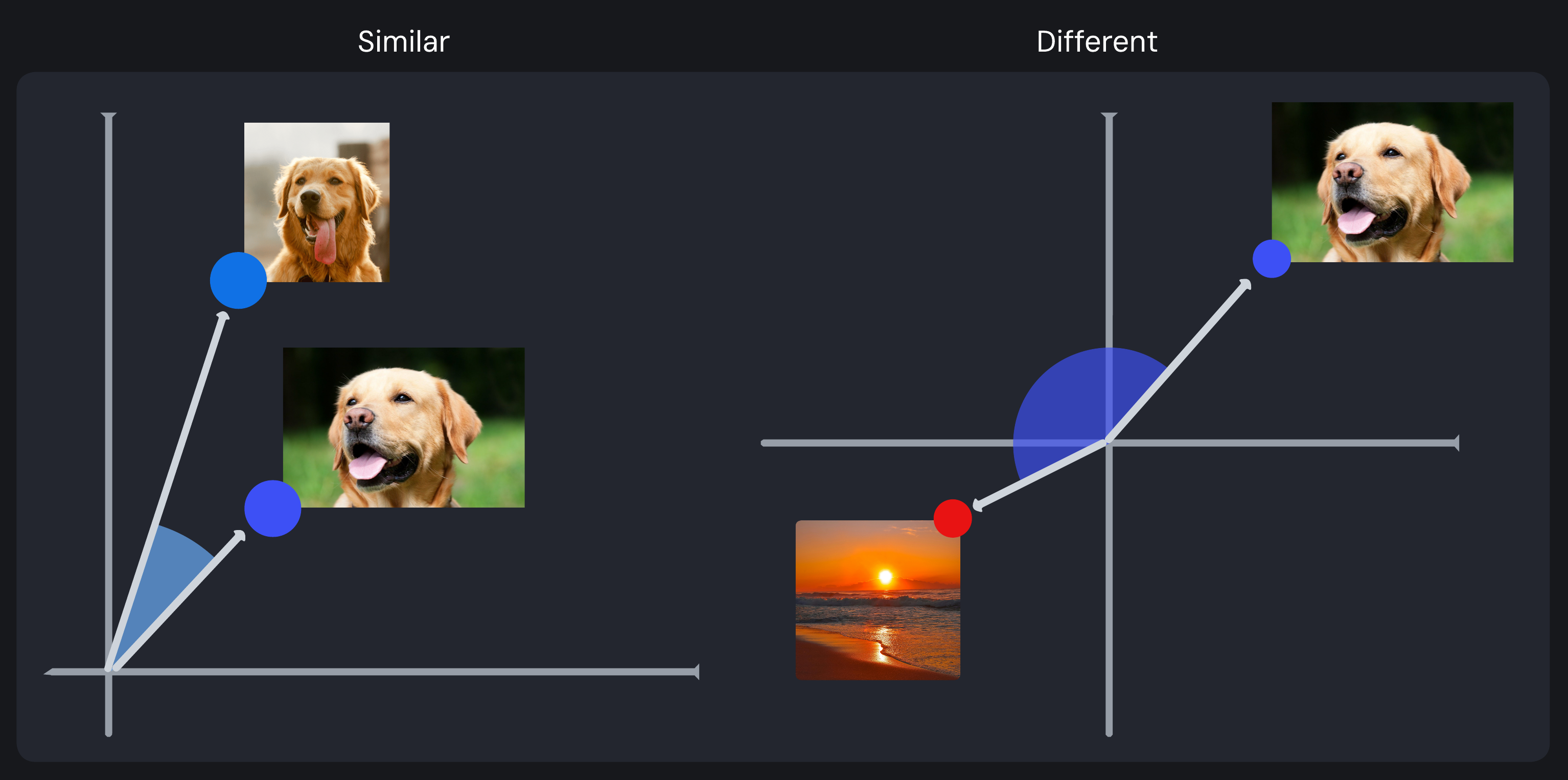

Cosine similarity measures the similarity between embedding vectors by evaluating the angle between them in a high-dimensional embedding space. Instead of focusing on absolute value differences, it assesses how aligned the directions of the vectors are. A small angle indicates the embeddings point in nearly the same direction, suggesting they share similar features, while a larger angle reflects significant differences. This technique simplifies complex relationships in high-dimensional space into an intuitive metric for quantifying similarity and ranking the most similar results (known as “nearest neighbors”).

Comparison of cosine similarity: similar vectors (two dogs) with a small angle versus different vectors (dog and sunset) with a large angle

Because each embedding represents the encoded features of a specific image, it’s important to restate here that similarity is determined by multiple visual characteristics of the input image (including aspects like texture, color, mood, and content), enabling more nuanced comparisons than would be possible with simple categorical matching alone.

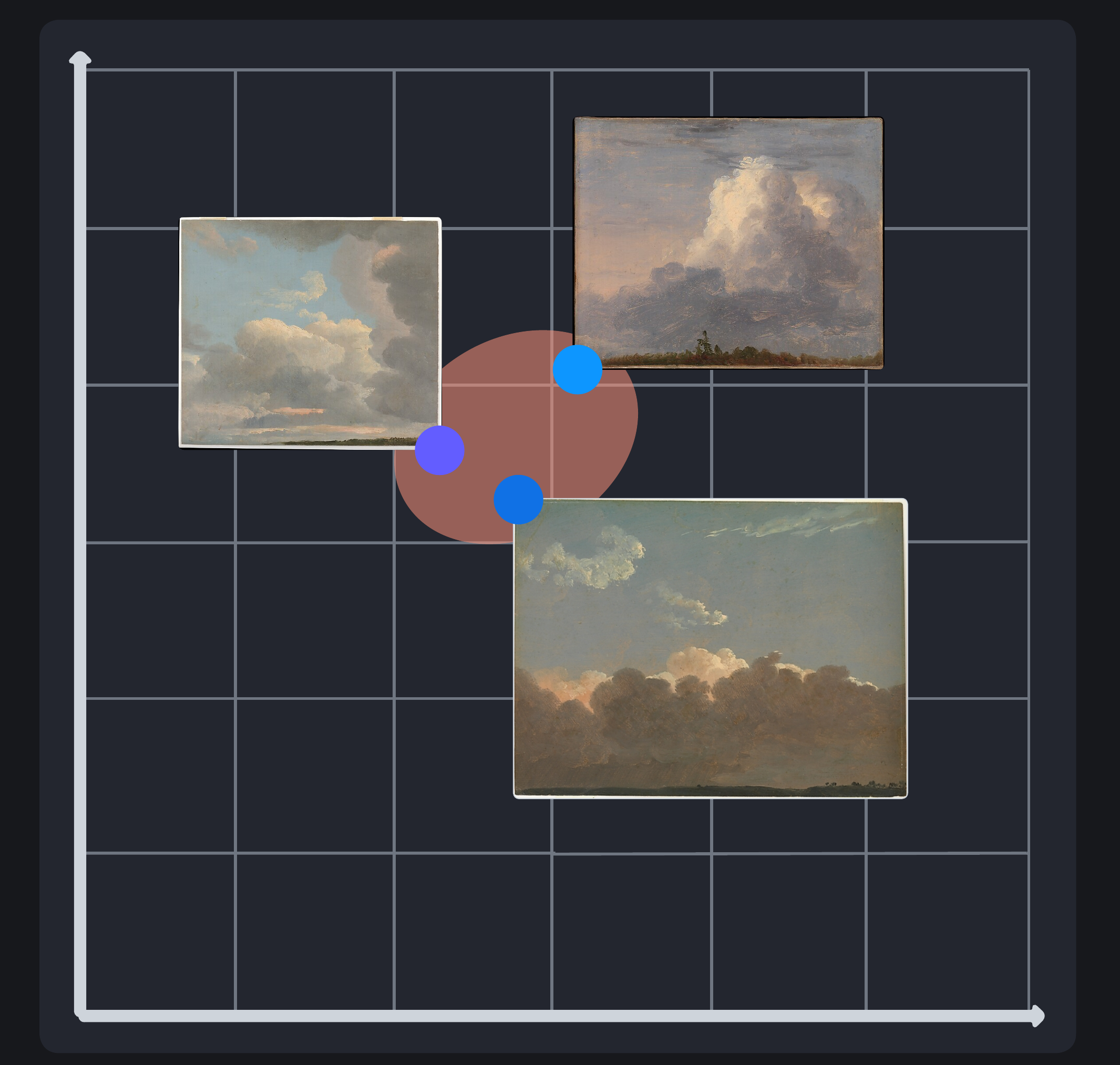

Similar cloud paintings clustered together in vector space (nearest neighbors)

An image organizational system that uses embeddings must first generate and store embeddings for all images in its dataset. Then, when a user uploads a photo to search with, the system must encode the search photo into an embedding and compare that embedding against the other stored images in the system to return the nearest neighbors or most visually similar images. However, this model is limited to only image-based queries, meaning a user must provide an image to find similar images. This leads us to the next technological evolution: multimodal embeddings.

Enter Multimodal Embeddings

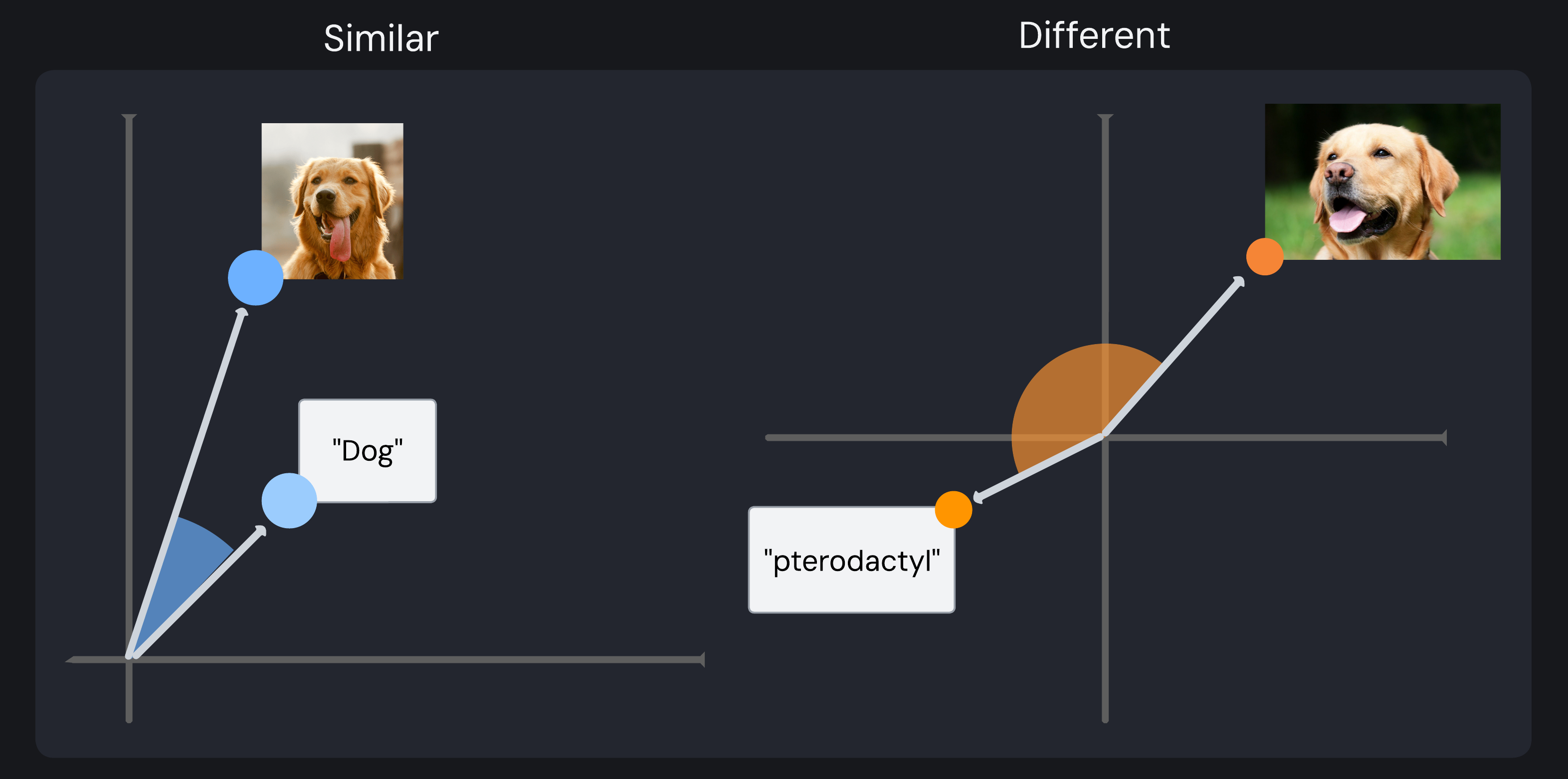

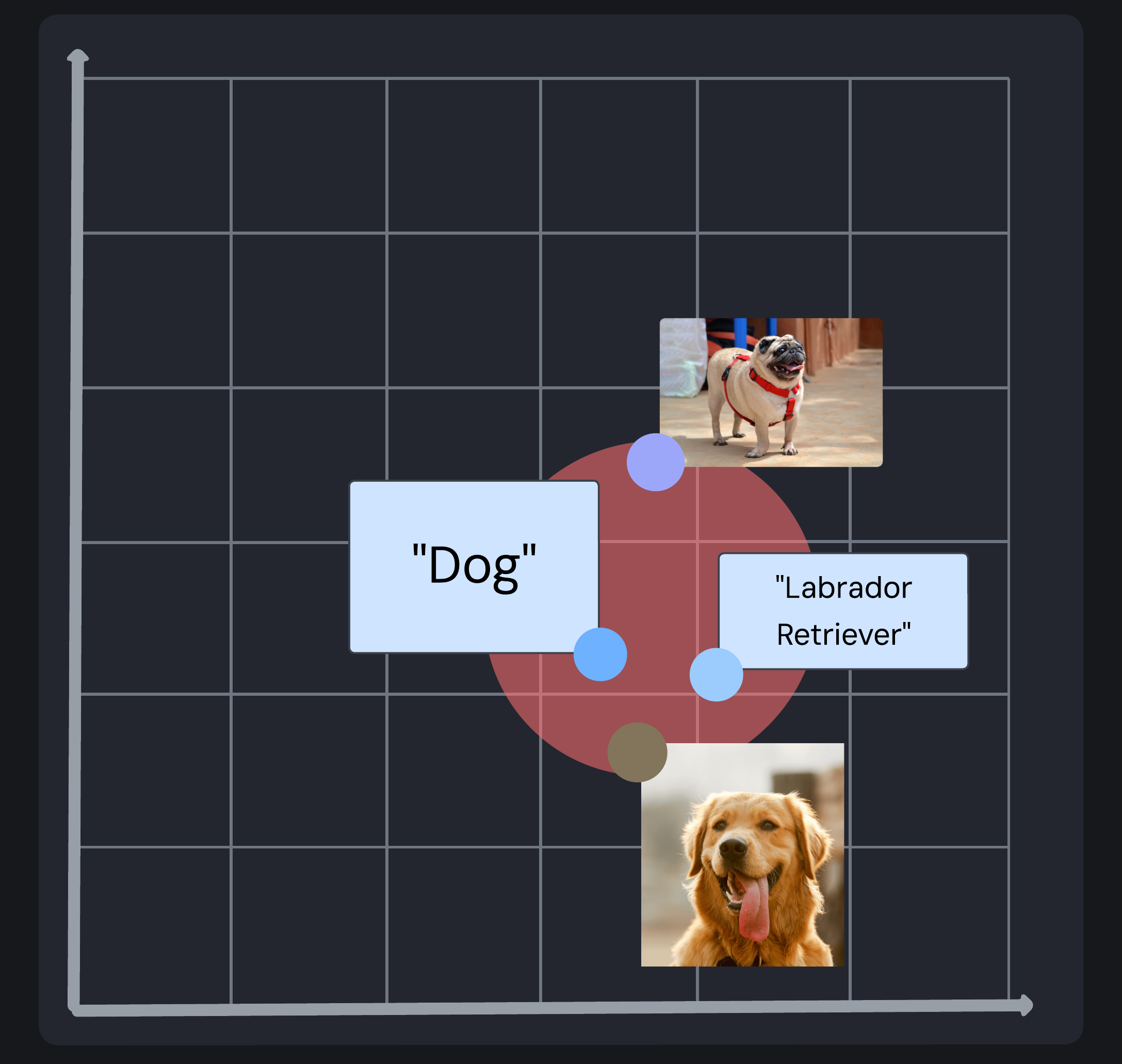

Multimodal embeddings combine data types, such as text and images, into a unified embedding space. Similar content is positioned close to each other, regardless of its original format. For example, a photograph of a Labrador Retriever and the word “Dog” could be located next to each other in this embedding space. This enables comparison of both formats based on their encoded features, effectively illustrating their similarities and differences.

Multimodal embedding comparison: similar vectors (“Dog” text and dog image) with a small angle versus different vectors (“pterodactyl” text and dog image) with a large angle

This technology is powerful because it enables users to search using whatever format feels natural - an example image, text description, or combination of both. In each case, the multimodal embedding model can create a search embedding to evaluate the most similar stored embeddings.

Semantic clustering of related dog (text and image) content in multimodal embedding space

Multimodal embeddings are particularly valuable for platforms that manage large collections of visual content, such as image-sharing sites (like Flickr and Pinterest), stock media marketplaces (like Envato), or platforms for user-generated art and designs (like Redbubble). By embedding visual and textual information into a shared embedding space, these systems provide more intuitive search results and enhance recommendations, improving user experience and content discoverability.

While powerful, multimodal image embedding search is not the right solution for all organizations. Small businesses with limited image catalogs (where simple categorization is likely sufficient) or businesses for which exact attribute matching is the primary search need (such as part numbers or technical specifications) may get limited benefit. Further, many successful implementations combine multimodal embeddings with traditional methods, balancing embedding-based semantic understanding with manual labels and user behavioral data.3